JOURNALS || Health & Medicine Blog (ASIO)

How Dhaka’s Dengue Struggle Became a Global Wake-Up Call: Climate, Environmental and Socioeconomic Fault Lines

Abdul Kader Mohiuddin (M. Pharm, MBA)

Alumnus, Faculty of Pharmacy, Dhaka University

Dhaka, Bangladesh

ORCiD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1596-9757

Web of Science ResearcherID: AAY-1094-2020

SciProfiles: 537979

Email: trymohi@yahoo.co.in

Mobile: +880-13468094645

Dengue transmission has intensified into a climate-driven global emergency, with statistical evidence showing an unprecedented rise in infections and deaths over the past decade.Over the last fifty years, dengue incidence has increased nearly thirty fold, reaching 6.5 million reported cases and more than 6,800 deaths worldwide in 2023, before surging even further in 2024, when the Americas alone recorded over 12 million cases and roughly 7,000 fatalities.Current estimates indicate that dengue now causes 400–700 million infections each year, claiming more than a million lives worldwide. Both the WHO and the U.S. CDC warn that roughly half of the global population lives in dengue-risk zones, providing clear evidence that climate change is reshaping the global geography of infectious disease.

The World Bank notes that since 1950, global mosquito transmission capacity has increased by roughly 9.5 percent, a rise driven largely by long-term warming trends. Climate factors—especially temperature, rainfall, and humidity—play a decisive role in shaping the ecology of dengue transmission. The risk of dengue climbs steeply when temperatures range between 25 °C and 35 °C, peaking near 32 °C, while monsoon-season humidity levels of about 60% to 78% from June through September significantly boost mosquito survival and viral replication, as documented in a Nature study. As warming continues, Aedes mosquitoes are expanding beyond their traditional tropical range, placing parts of Africa, southern China, the Americas, and even regions of the United States at growing risk and raising alarm towards the increased global nature of the threat.

Bangladesh exemplifies this shift, with dengue surging dramatically since 2018 and mirroring global trends. National temperatures have risen by roughly 0.5°C over the past four decades, lengthening the dengue season and contributing to case numbers that have doubled approximately every decade since 1990. Between 2018 and 2025, dengue evolved from a sporadic illness into the country’s deadliest post-COVID infectious disease. Experts caution that the unusually high rainfall observed in October from 2022 to 2025 further intensified the crisis, serving as a clear indication that climate shifts are exacerbating transmission.

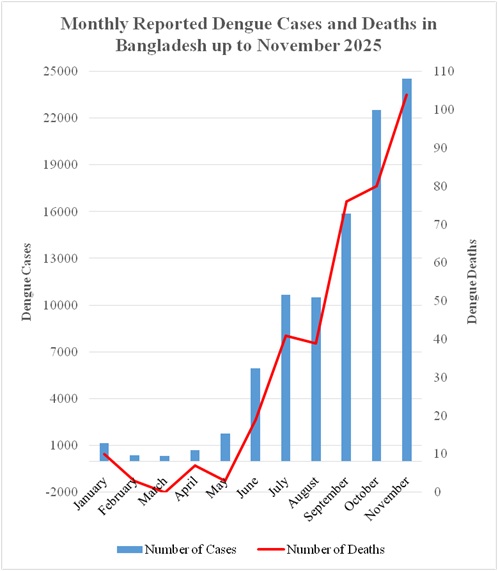

Since 2023, data from the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) show that Bangladesh has recorded more than half a million dengue infections, with nearly 2,700 lives lost. The scale of the crisis became starkly apparent in 2023, when over 321,000 people were infected and 1,705 died—more than twice the total deaths recorded between 2000 and 2022 combined—ranking Bangladesh third worldwide in the number of dengue cases.The human cost is escalating alongside systemic failures. Bangladesh is facing an unprecedented dengue emergency. Hospitalizations nearly quadrupled between June and October 2025, pushing an already strained health system to the brink, while dengue deaths surged by 150% YOY by September. The crisis peaked in November. On 18 November alone, hospitals were overwhelmed by more than 900 viral fever patients alongside nearly 3,000 active dengue cases. By the end of November 2025, over 24,500 infections and 100 deaths had been recorded (Figure 1)—more than a quarter of the year’s total cases and fatalities concentrated in a single, devastating month—according to DGHS dynamic data.

Click here to Download-Figure 1. Monthly Incidence of Dengue Cases and Dengue-Related Deaths in Bangladesh up to November 2025 (Source: DGHS). The figure shows a sharp rise in dengue cases and deaths beginning in June, with reported infections nearly quadrupling by October. The situation peaked in November 2025, when more than 24,500 cases and 100 deaths were recorded—over a quarter of the year’s total burden concentrated in a single month.

The capital, Dhaka, accounted for more than half of all cases and nearly 70 percent of fatalities in 2023, despite its two city corporations having spent over $80 million on mosquito-control efforts over the past decade. These grim outcomes point to deeper systemic failures, including a lack of public awareness, inadequate hospital staffing, limited healthcare capacity, delayed diagnoses, weak and poorly coordinated vector-control measures, insecticide resistance, false negatives in NS1 tests, limited access to effective vaccines, the absence of strategic planning, failure to follow WHO guidelines, and persistent corruption and negligence, all compounded by the exclusion of qualified public health professionals from decision-making.

Environmental degradation has magnified this trajectory by reshaping mosquito habitats. Dhaka lost more than 50% of its green cover between 1989 and 2020, contributing to extreme heat accumulation and a near doubling of ≥35 °C heat days over three decades. The city’s heat index has risen over 65% faster than the national average, creating conditions in which Aedes mosquitoes adapt to heat and develop greater viral tolerance. Similar urban heat-island effects are now documented across fast-growing tropical cities worldwide.

The WHO estimates that nearly a quarter of human diseases and deaths result from long-term exposure to pollution. Dhaka struggles with air pollution, worsening air pollution in winter, which eases during the monsoon. Research has found that in cities worldwide—such as Taiwan, Singapore, Guangzhou, Northern Thailand, Melaka, and São Paulo—air pollutants, including PM2.5, O?, SO?, CO, and NOx, interact with climate factors to affect mosquito activity, virus transmission, and human vulnerability.

Socioeconomic pressures further intensify transmission by amplifying human–vector contact. Dhaka, with over 75,000 people per square mile, ranks among the world’s secondmost densely populated cities, while more than 40% of Bangladesh’s population now lives in urban areas, over half in informal settlements. Nationally, one-third of residents lack safely managed sanitation, and an estimated 230 tons of fecal waste enter Dhaka’s drainage system each day, which is already about 70 percent clogged due to its unplanned structure and excessive length—at least four times longer than the country’s longest north–south axis—according to findings from UNICEF and the Institute of Water Modelling, a wing of the Ministry of Water Resources. Furthermore, infrequent water supplies in dense urban areas force residents to store water. These conditions ensure that even moderate rainfall produces persistent Aedesbreeding sites, a pattern mirrored in densely populated cities across South and Southeast Asia.

Waste mismanagement and water pollution add a critical, under-recognized layer of risk. Approximately 55% of urban solid waste in Bangladesh remains uncollected, while rivers such as the Meghna, Karnaphuli, and Rupsha collectively discharge nearly one million metric tons of plastic annually. The country contributes 36 rivers to the global network responsible for roughly 80% of river-borne plastic emissions, as per-capita plastic consumption tripled between 2005 and 2020, with the COVID-19 pandemic adding more than 78,000 tons of polythene waste. Emerging evidence from researchers at the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology indicates that microplastics may disrupt mosquito development and reduce susceptibility to insecticides, potentially accelerating transmission under polluted conditions.

Dhaka’s rapid, largely unplanned urban expansion has created near-perfect conditions for Aedes mosquitoes. Prior to 2016, an average of 95,000 new structures were erected annually within RAJUK’s jurisdiction, while at least 64,000 constructions have taken place since 2008. A joint inspection by the National Malaria Elimination and Aedes Transmitted Disease Control Programme under the DGHS found that nearly 70% of homes and construction sites across 55 wards harbored potential Aedes breeding sites.

The following year, a DGHS survey spanning 70 areas of Dhaka reported that high-rise buildings accounted for more than 45% of these sites, followed by under-construction structures at nearly 35%. In 2024, the former DSCC Mayor issued warnings that construction activities would be halted wherever Aedes larvae were detected. The latest pre-monsoon survey, conducted collaboratively by the DGHS and the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR), paints a similarly alarming picture: multistory buildings now account for almost 60% of Aedes larvae, with an additional 20% found in under-construction sites.Without exception, many densely populated cities worldwide—mostly in the tropics—are experiencing a troubling surge in mosquito-borne diseases, particularly dengue.

Looking forward, projections paint a stark global warning. Climate models reported in a Nature study suggest that by 2080, nearly three in five people worldwide could be exposed to dengue risk, as rising temperatures, prolonged monsoons, and unplanned urbanization allow mosquito habitats to expand into new regions and higher elevations.What is unfolding in Bangladesh reflects a broader planetary pattern in which climate instability, environmental degradation, and socioeconomic vulnerability converge to threaten human life. Dengue has thus become a sentinel disease of climate change—signaling that without urgent, coordinated global action, today’s outbreaks may foreshadow a far more devastating future.

ABBREVIATIONS

DGHS: Directorate General of Health Services

DSCC: Dhaka South City Corporation

IEDCR:The Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research

NS1: Nonstructural Protein 1

RAJUK:Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha

WHO: World Health Organization

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from the Dengue Dynamic Dashboard for Bangladesh, maintained by the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), Health Emergency Operation Center & Control Room. These data are publicly available at: https://dashboard.dghs.gov.bd/pages/heoc_dengue_v1.php

Published on: 12/01/2026